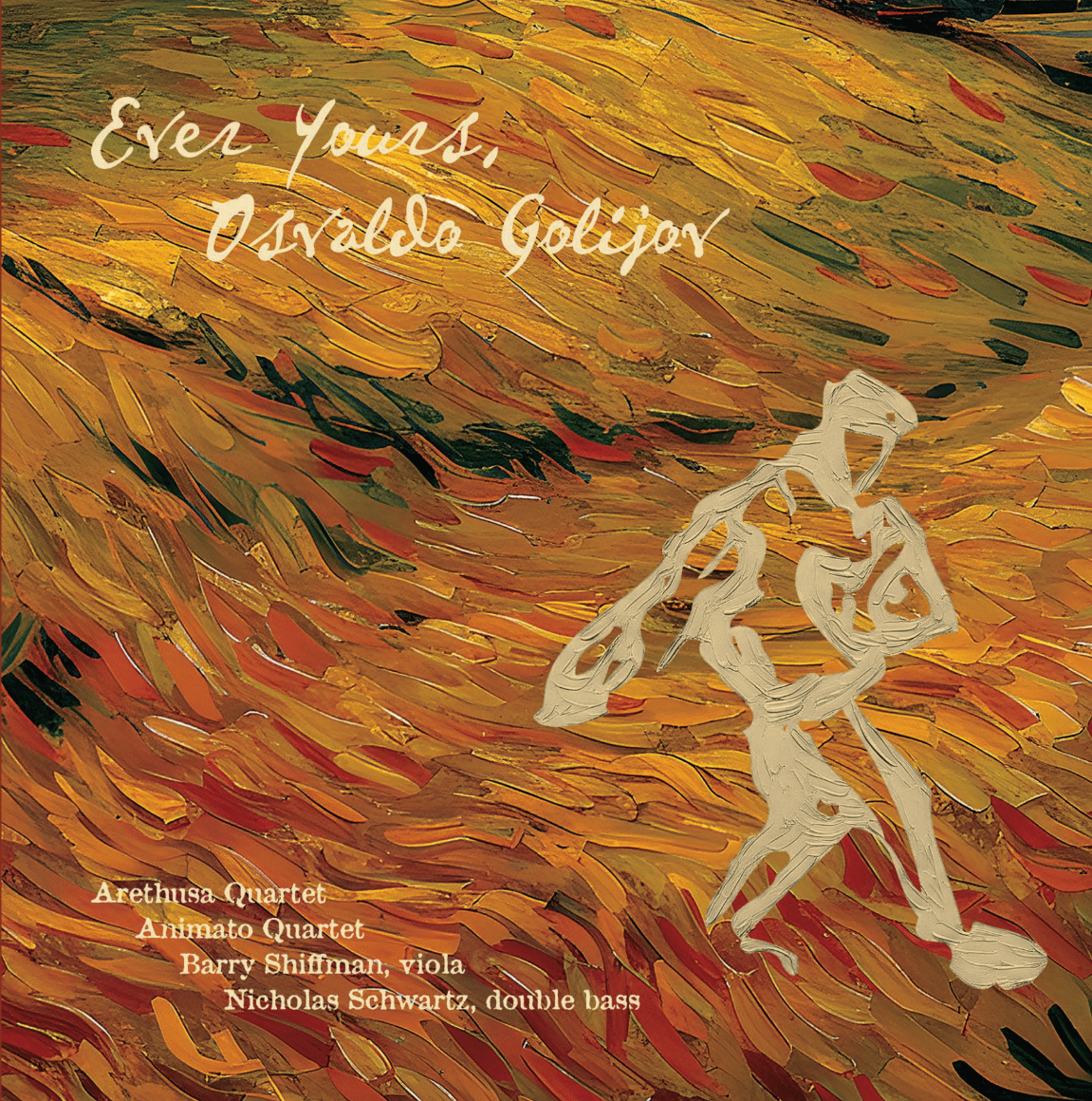

Ever Yours ~ Liner Notes

Oswaldo Golijov ~ Ever Yours

Composer Notes

Ever yours

In its original version (2022) for string octet, Ever Yours was the last piece I wrote for and dedicated to Geoff Nuttall, who was, and still is, my brother in music and life.

I was inspired primarily by two things: brotherhood, as embodied in the letters that Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo—which he always signed with the words “Ever Yours”—and the String Quartet, Op. 76, No. 2 by Joseph Haydn, who was the composer Geoff loved and admired the most.

Op. 76, No. 2 is, to my mind, a love letter to music. Its first movement is built entirely on two pairs of notes: A-D/E-A. The interval (distance) between the notes in each pair is a fifth, and that’s why this quartet is nicknamed “Quinten” [Fifths]. The fifth is not just an interval that Haydn chose at random among the twelve possibilities he had; it is the interval on which the grammar of the classical tonal language is built. Haydn’s prodigious powers of invention unveil many contrasting worlds born from those two pairs of fifths. For the first movement in Ever Yours, I have passages from Haydn’s first movement pass through a metaphorical prism, and thus new worlds are generated.

As Geoff was dying while I was writing the piece, I remembered the following passage from van Gogh’s letters: “Why, I say to myself, should the spots of light in the firmament be less accessible to us than the black spots on the map of France. Just as we take the train to go to Tarascon or Rouen, we take death to go to a star.” So, for the second movement in Ever Yours, I place the theme of Haydn’s second movement in Op. 76, No. 2 under a metaphorical microscope. Doing this reveals enormous distances between the notes in the original, and makes hearable vibrations akin to interstellar dust that are inaudible in it. What in Haydn is a beautiful jewel becomes in Ever Yours an immense journey to the stars.

The third movement in Haydn is a canon in two parts (“Frère Jacques,” for instance, is an example of a canon). In the third movement of Ever Yours I multiply the numbers of parts in that canon, sometimes to four, sometimes to six, and sometimes, if I remember correctly, even to eight parts. In the process of this canon proliferation, a passage from Beethoven’s last quartet, Op. 135, emerged—to my surprise and to no surprise.

For the last movement of Ever Yours I took just a short, 4-note figure from Haydn’s fourth movement. This figure contains an augmented second interval, which is typical of the popular Hungarian Roma music that Haydn loved to quote in some of his finales. I made a bass ostinato (a sort of loop) in an odd meter (7) with those four notes and had the upper strings dance, growl, and bark at each other. Somehow a memory of my uncle’s 17 dogs greeting me when I would visit him resurfaced while I was writing this movement, so passages of this fourth movement are based on that memory.

I wrote Ever Yours, primarily, as a conversation about music, Haydn, friendship, life, and death, between Geoff and me. Geoff is now gone, and his (and my) beloved St. Lawrence String Quartet, which he co-founded and led for more than 30 years, has disbanded. But the idea of a conversation between friends continues to live in this new version of the work. I feel blessed to have encountered relatively late in life new true friends: the members of the Arethusa and Animato quartets, and bassist Nicky Schwartz. The days we spent recording this piece, guided by Stephen Prutsman, another dear old friend of Geoff and me, were joyous and poignant. I am immensely grateful to all of them, as I am to Shawn Conley, who helped me arrange the bass part, and to Yasmin Hilberdink, director of the Amsterdam String Quartet Biennale, Monica Rosenzweig Armour, the University of Maryland, and the San Francisco Conservatory, for commissioning this work.

Tintype

Early in the summer of 2024 I received an invitation from Oren Rudavsky to compose a theme for the soundtrack to his documentary, Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire.

I was inspired by several animated dream sequences in the film, in which Elie dreams of his father, who died in the Holocaust. They are full of sentiment, but not sentimentality. That is a feeling I get when listening to the second movement in Schubert’s E-flat Piano Trio. I wrote a theme based on that movement, in which I also wanted to explore the particular kind of density that Mozart unveiled in his string quintets with two violas. Something like an endless melancholy walk emerged.

The theme kept growing and became what is now the second movement of Tintype. I couldn’t stop writing and composed two more movements. The first is based on a traditional Hebrew melody, which Joseph Achron transcribed and arranged in the first decade of the twentieth century and violinists such as Jascha Heifetz and Josef Hassid popularized in their recitals. My version starts ghostly, representing a vanished world. It then comes to full life, before vanishing again. The third movement is based on a version of the prayer, “Ani Maamin” [I Believe], that Elie Wiesel sings in the last minutes of the documentary. Here, it alternates between sparse, expressionistic fragments of the prayer, and driven, motoric sections inspired by Philip Glass’s string writing. I hear the spirit of Schubert in his chamber music, as I hear it in my own music.

K’vakarat

I wrote the original version of K’vakarat in 1993 for cantor Misha Alexandrovich and the Kronos Quartet. It then became the last movement of my clarinet quintet, The Dreams and Prayers of Isaac the Blind, which I wrote in 1994. Almost 30 years later my dear friend Barry Shiffman, who co-founded with Geoff Nuttall the St. Lawrence String Quartet, decided to arrange the piece for viola and string quartet.

“K’vakarat” [As a Shepherd…] is a prayer from the Yom Kippur liturgy, in which God is compared to a shepherd. He decides who among the sheep of his flock will live, and who will die. I use the traditional melody as a refrain which appears three times, interpolated by cadenza-like interludes. The first two times the refrain in the melody is accompanied by a sublimated shepherd’s flute I create for the quartet. The last time the flute is transformed into a sword, to rebel against the meaning of the text and, as it happens sometimes in the Jewish tradition, to wrestle with God.

Esperanza

Esperanza [Hope] is the love theme I composed for the soundtrack of Francis Ford Coppola’s film Megalopolis. Francis wanted “something like Romeo and Juliet, but geometric.” I came up with an almost abstract theme, which could be transformed according to what was needed for the different film scenes in which it appeared. It is a yearning, 4-note motif, which finds an elusive resolution after three ascending repetitions. This version was not planned for the recording. It happened because I was so exhilarated by working with the Arethusa and Animato quartets, and bassist Nicky Schwartz, in Amsterdam during the third week of January 2025. One early morning in the hotel before going to the studio, I decided to arrange the theme in this version for them—as an expression of my gratitude for their musicianship and heart.